In law school, we are taught that hearsay deals with out of court statements. Both the Federal Rules and California’s Evidence Code define hearsay as a “statement” that is “offered to prove the truth of the matter” either “stated” (California) or “asserted” (Federal). And on most occasions, hearsay involves a “statement” as that term is generally understood. In other words, most hearsay evidence involves instances where a party or witness either said or wrote something. As a result, practitioners keep their eyes and ears open for out-of-court oral or written communications. While this is not wrong per se, thinking of “statement” in the ordinary sense results in both (1) false positives (i.e., incorrectly identifying a communication as hearsay when it isn’t), and (2) false negatives (i.e., missing objectionable hearsay). To better identify objectionable hearsay, it’s imperative to understand what is meant by the term “statement.”

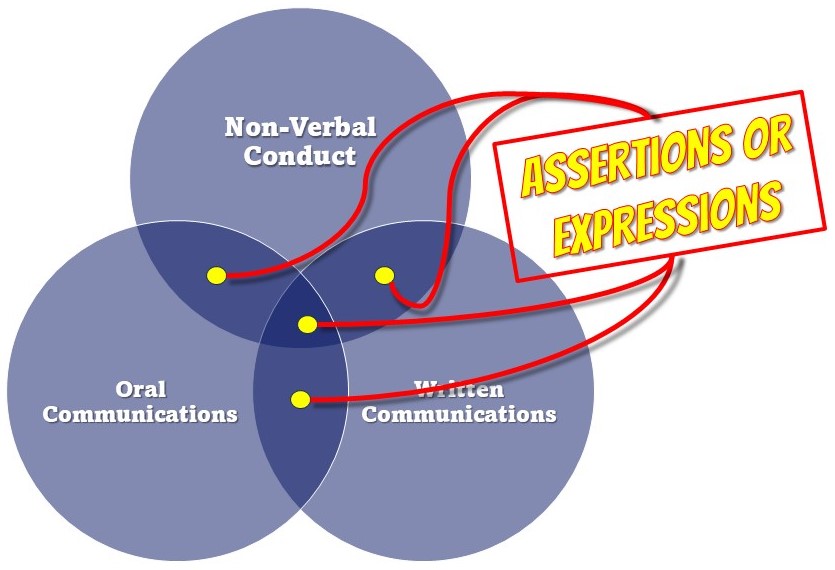

Statement = Assertion or Expression

The moment lawyers (and sometimes judges) spot any communication made “out of court,” they can quickly get bogged down looking for potential hearsay exceptions. “Statement” as defined by the hearsay rule, however, is not any communication. In the Federal Rules, “statement” is defined as “a person’s oral assertion, written assertion, or nonverbal conduct, if the person intended it as an assertion.” Fed. R. Evid. 801(a). In California, “statement” is defined to include “(a) [an] oral or written verbal expression, or (b) nonverbal conduct … intended … as a substitute for oral or written verbal expression.” Cal. Evid. Code § 225. A question is not an assertion (or expression). An instruction is not an assertion (or expression). An assertion (or expression) is something someone says or does in order to communicate (1) a fact, or (2) an opinion that is intended to be accepted as true or accurate. In other words, when analyzing whether something is a “statement,” the focus is on the intended message. A more practical way to identify hearsay is to look for an out of court assertion or expression.

Statement = Nonverbal Assertion

When the focus is on whether the out-of-court communication was intended to assert or express a fact, it becomes more intuitively obvious that non-verbal conduct can also constitute a “statement” for purposes of the hearsay rule. For example, suppose a case involved allegations that a certain type of medicine to treat headaches was causing heart attacks. The defense wants to introduce testimony that the person who invented the medicine had taken the medicine himself. The defense calls a colleague of the inventor who seeks to testify, “I saw the inventor take the medicine.”

The evidence is relevant because if the inventor is willing to take the medicine, such conduct implies that the medicine is safe. But could it be hearsay?

We have a declarant (i.e., the inventor) engaging in out-of-court non-verbal conduct, and it’s not obvious from him simply taking the medicine that he intended to assert or express anything specific. But what if there was an out-of-court statement just before the inventor took the medicine. Suppose the witness wished to testify, “I heard the inventor say, ‘I have a pounding headache,’ and then I watched him take the medicine.” We have a statement: the inventor asserting that he has a pounding headache. In this case, we’re told that the plaintiff is alleging that the medicine causes heart attacks, and the defense wishes to introduce the fact that the inventor took the medicine to prove the medicine is, in fact, safe. Turning to the statement, “I have a pounding headache,” is the defendant offering the statement to prove the inventor had a pounding headache? Not at all. Whether the inventor did or did not have a headache has nothing to do with whether the medicine is safe. Put another way, the defense is not offering the statement “to prove the truth of the matter [i.e., the existence of a headache] asserted.” Thus, no hearsay, and the taking of the medicine is not objectionable.

Now suppose the witness instead wished to testify, “I asked the inventor whether the medicine was safe. The inventor said, ‘You think this medicine is dangerous? Watch this! And then he took the medicine.” Hearsay?

We now have several out-of-court statements to consider. As a general rule, each assertion within a narrative is typically considered in a hearsay analysis. Exceptions to the assertion-by-assertion rule occur when the hearsay focuses on the nature of the speaker (e.g., once a declarant is deemed a co-conspirator, the hearsay rule no longer applies). In this case, each assertion must be considered:

First, the witness testifies, “I asked the inventor whether the medicine was safe.” Although the witness is on the stand, he or she is repeating a prior out-of-court verbal communication. However, the communication was a question, not an assertion, and therefore not a “statement” as defined by the hearsay rule.

Second, the inventor told the witness, “You think this medicine is dangerous?” Again, we have an out-of-court communication that is framed as a question. The inventor then says, “Watch this!” Typically, when a person makes a commend or gives a direction, the purpose is not to assert anything (e.g., “Turn left at the light.” “Please pass the salt.”) Such commands or directions are sometimes called “non-assertive verbal conduct.” The phrase, “Watch this!” in isolation appears to simply be a non-assertive verbal direction.

Of course, human communication is complex. People can be intentionally sarcastic, saying one thing but meaning the exact opposite. In our current hypothetical, it is obvious that the inventor’s intended communication—even though each individual component is a question, a direction, and non-verbal conduct—is that the medicine is safe. When a declarant’s words or conduct (or a combination) implies a fact, it is deemed an assertion (i.e., it constitutes a statement). Thus, the communications and conduct (taking the medicine) would constitute a “statement” under the hearsay rule.

Conclusion

Simply looking for a “statement” in the general sense can miss the mark in a hearsay analysis. Especially in the heat of trial, recognizing objectionable hearsay within seconds is imperative. The simplest way to spot hearsay with better accuracy is to instead look for out-of-court assertions or expressions.

David Sugden is a shareholder at Call & Jensen in Newport Beach, California.