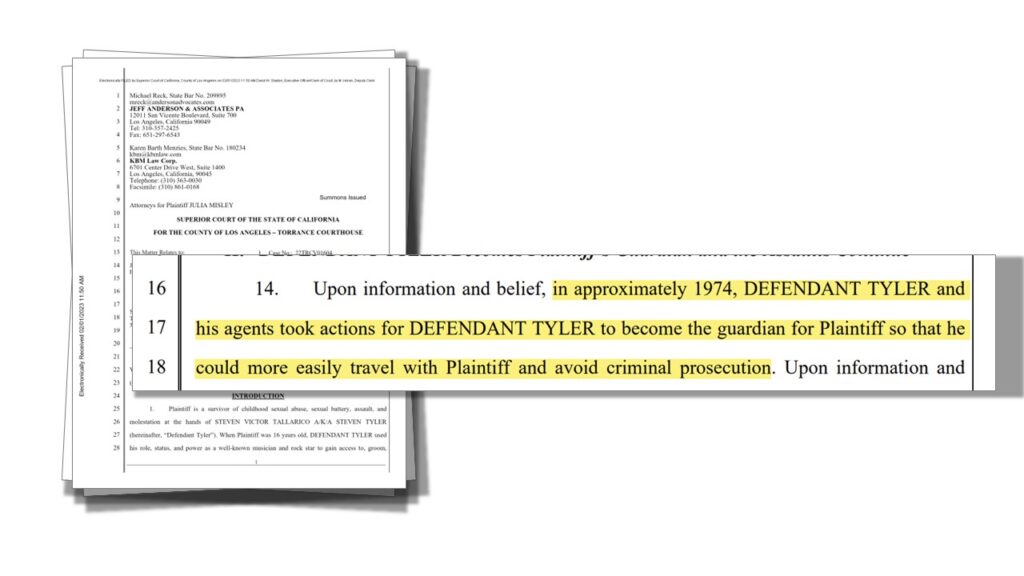

A few months ago, the Los Angeles Times ran a story about a lawsuit recently filed against Steven Tyler. The plaintiff alleges she met the Aerosmith frontman backstage in 1973, and she chronicles their relationship that evening and thereafter. According to the plaintiff, Tyler talked her into joining him on the road (after she finished her sophomore year in high school) and “persuaded [her] into believing this was a ‘romantic love affair.'” The complaint is remarkably detailed given the passage of time. For example, the plaintiff alleges that Tyler became her guardian in 1974 so that “he could more easily travel with Plaintiff and avoid criminal prosecution.”

Steven Tyler filed his responsive pleading this week. Procedurally, it’s a nothing burger. It’s the civil equivalent of pleading “not guilty” to criminal charges. The filing is typically (and predictably) generic. Without stating any facts, he denies the allegations and provides a laundry lists of affirmative defenses. This is standard practice for state court defendants in civil cases. To learn Tyler’s version of events, it appears that discovery will be necessary. And given the age of the allegations, what will Tyler remember? Beyond the years, how about Tyler’s cognition then? Tyler once explained to GQ Magazine his pre-concert routine from that era: “Well, we would do cocaine to go up, quaaludes to come down. We would drink and then snort some coke until we thought we were straight. But that’s not true—you’re just drunk and coked out.” Not exactly a superfood diet. But even if he spent the 1970s eating broccoli and taking fish oil supplements, what details can he reasonably be expected to provide beyond the basic denial in this week’s filing? The plaintiff will surely face an uphill battle in this anticipated she-said-he-said case.

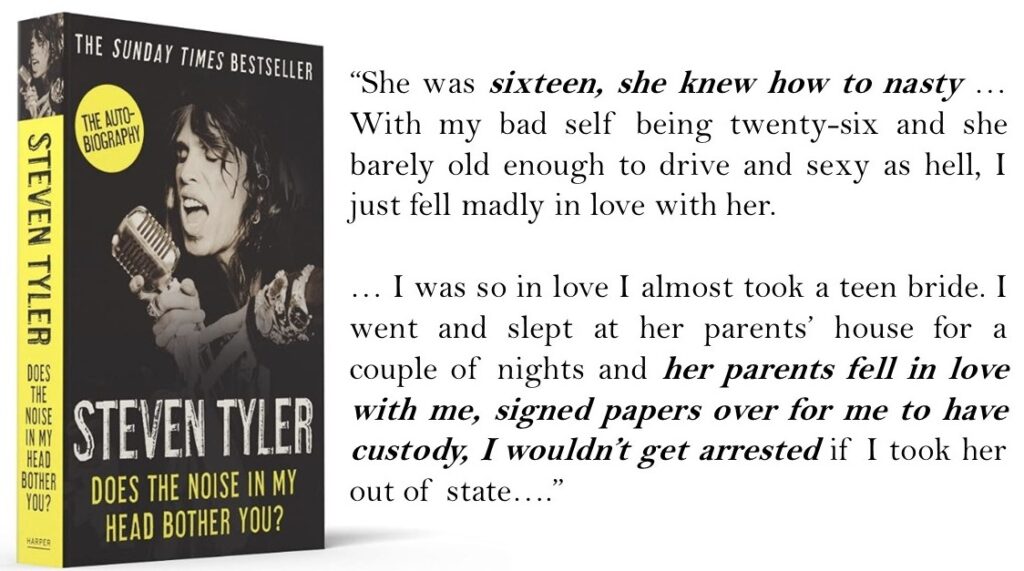

But maybe not. Perhaps Tyler has already done some of the plaintiff’s heavy lifting when he decided to pen his memoir. In 2011, Tyler wrote his autobiography, Does the Noise in My Head Bother You?, because “I have so many outrageous stories, too many, and I’m gonna tell ’em all. All the unexpurgated, brain-jangling tales of debauchery, sex & drugs, transcendence & chemical dependence you will ever want to hear.” Adhering to the sentiment that trashy events deserve to be retold, Tyler (according to the plaintiff’s complaint) chronicled the crimes he perpetrated on her. After identifying her by name in the book’s acknowledgments, Tyler wrote in Noise that, “[s]he was 16, she knew how to nasty … with my bad self being twenty-six and she barely old enough to drive and sexy as hell, I just fell madly in love with her… She was my heart’s desire, my partner in crimes of passion… I was so in love I almost took a teen bride. I went and slept at her parent’s house for a couple of nights and her parent’s fell in love with me, signed paper over for me to have custody, so I wouldn’t get arrested if I took her out of state. I took her on tour with me.”

Like class and dignity, Tyler probably did not give a second thought to any statutes of limitations when he penned Noise. He likewise had no reason to anticipate that, in 2019, California would provide a three-year window to revive certain time-barred claims. But does Noise provide the plaintiff with actual usable evidence?

Tyler’s Autobiography: An Evidentiary Analysis

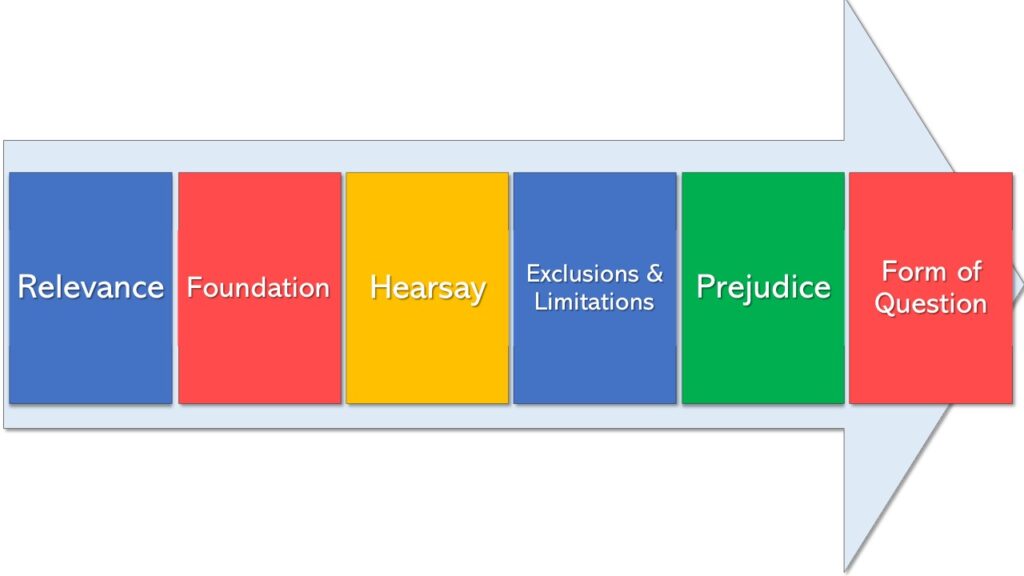

When it comes to analyzing the admissibility of evidence, having a methodical approach is imperative. Especially in the heat of trial, the ability to quickly (and accurately) analyze admissibility is a must-have skill. The figure below illustrates the approach:

That Tyler’s book excerpts are relevant is almost self-evident. The fact that he is writing about his (alleged) conduct with the plaintiff has a “tendency in reason to prove … [a] disputed fact that is of consequence to the action.” Cal. Evid. Code § 210. There will likewise be no reasonable dispute about foundation; the book is authored by Tyler. See Cal. Evid. Code § 1400 (“Authentication of a writing means (a) the introduction of evidence sufficient to sustain a finding that the document is what the proponent of the evidence claims it is….”). But what about hearsay? The writing is obviously an out-of-court statement. See Cal. Evid. Code § 1200 (“‘Hearsay evidence’ is evidence of a statement that was made other than by the witness while testifying….”). And the plaintiff would offer the relevant portions into evidence “to provide the truth of the matter stated.” Id. So is the evidence inadmissible?

A common exception to the hearsay rule in California (and considered “not hearsay” in federal court) is the party admission. California Evidence Code section 1220 states that “[e]vidence of a statement is not made inadmissible by the hearsay rule when offered against the declarant in an action which he is a party in either his individual or representative capacity, regardless of whether the statement was made in his individual or representative capacity.” In Irving Younger’s Hearsay: A Practical Guide Through the Thicket, he provides a simpler “rule of thumb.” Younger explains that “[a]nything the other side ever said or did will be be admissible so long it has something to do with the case.” Unlike other lay testimony, where it must be based on personal knowledge, party admissions are admissible even if the party lacked personal knowledge of the facts then-admitted. The rationale behind the rule is the idea that people do not make significant statements of fact unless they are true. See Levy-Zentner Co. v. Southern Pac. Transp. Co., 74 Cal. App. 3d 762, 786 – 787 (1977). So even if Tyler swears that the book was fiction, and that the plaintiff’s allegations are made up (and based on his book), such an argument would not warrant excluding the relevant passages from admission.

Party Admissions v. Judicial Admissions

Party admissions are evidentiary admissions, which are distinguishable from judicial admissions. A party admission is a piece of evidence that the jury considers and weighs against all other conflicting evidence. Thus, Tyler’s admissions in Noise will be admissible along with whatever testimony he wishes to offer that contradicts or provides some mitigating context. A judicial admission, on the other hand, conclusively establishes certain facts (and cannot be contradicted). For example, a party is conclusively bound by allegations made in its pleadings (in the current litigation). See e.g., Fuentes v. Tucker, 31 Cal. 2d 1, 5 (1947). Thus, parties may not introduce evidence contrary to their own pleadings. Id. at 4. The difference is significant. If the same language found in Noise was in Tyler’s responsive pleading, the plaintiff could file a motion in limine to bar Tyler from introducing any contradictory evidence. See e.g., Thurman v. Bayshore Transit Mgmt., Inc., 203 Cal. App. 4th 1112, 1156 (2012) (Plaintiff was bound by judicial admissions in his complaint where, in opposing defendants’ motion in limine, he had indicated he would move for leave to amend the complaint but never did).

Conclusion

Given the party admission rule, Tyler and his legal team will need to contend with his musings in Noise. In fact, given the plaintiff’s allegation that her relationship with Tyler began in 1973, he may need to explain some of the lyrics from the band’s 1975 hit Sweet Emotion. “I pulled into town in a police car[, and] Your daddy said I took it just a little too far” has not exactly aged well.

David Sugden is a shareholder at Call & Jensen in Newport Beach, California.